HOCC

Towards Constructive Theory of Finitary Pure Sets (draft)

Alexander Kuklev, JetBrains Research

In this paper, we first briefly summarize the history of set theories, explaining why and how they were used as a foundational system for the whole of mathematics and why they still matter when modern type theory based systems take over their role as the foundations. Then, we develop a constructive variant of the non-Gödelian set theory $H_{<ω}$ [Pakhomov2019] of finitary pure sets that comprises the common core of all set theories used to model mathematical objects, including CZF. We suggest that this theory and can be used to carry out conditional consistency proofs instead of weak arithmetic theories ($S_1^2$, ERA) while being strictly weaker and able to proove its own consistency.

§ Introduction

In structuralist foundations of mathematics, there are objects of very different types: natural numbers, various combinatorial objects (e.g. finite strings of balanced brackets like “()((())())”), real numbers, tuples, lists, functions between any types, relations on any types, and so on. The vast zoo of types made structuralist foundations unattractive until 1990ies when the burden of type bookkeeping could be delegated to computers. Instead of dealing with a complex type theory underlying structuralist foundations, one could take a theory $S$ of one particular type of objects that are rich enough to model all types of intrest (natural numbers, functions, relations, etc) and substitute all other types by their $S$-models.

That is precisely how Cantorian set theories were used as foundation for the whole mathematics for more than a century. Let me briefly remind what Cantorian set theories are and how they came to existence.

§§ From Cantor’s Naïve Set Theory to ZFC

Any kind of foundations necessarily deals with sets of natural numbers, sets of reals, and other sets of objects of specified type. Finite sets are just finite lists ignoring order and multiplicity. That is one takes finite lists, defines the predicate (_ $∈ l$) «_ is an element of $l$», and defines finite sets as lists modulo equality relation $(l_1 = l_2) := ∀(x) (x ∈ l_1) ⇔ (x ∈ l_2)$. How could infinite sets be defined? The conventional approach is to identify them to predicates on their elements’ type: every predicate $φ(x)$ on the type $T$ defines a set { $x : T | φ(x)$ }, while every set $S$ defines a precidate (_ $∈ S$) on the type $T$, and sets with same elements are equal ( $(a = b) := ∀(x) (x ∈ a) ⇔ (x ∈ b)$, which is known as extensionality). Thus, sets just reflect predicates.

Already in the 18th centory, it was recognized that one can also study pure sets, i.e sets consistung of sets, consisting of sets, and so on. It might appear that this recursion has to lead ultimately to some fixed non-set type, but that is a false impression because there is at least one object that surely exists and qualifies as a pure set: the empty set.

Finitary pure sets are simple combinatorial objects built by wrapping the empty set in various ways. For example one can consider the set containing the empty set as element {∅} and the set containing this set { {∅} } or the set containing both of them { {∅}, { {∅} } }. Finitary sets can be seen as unlabeled trees of finite width and depth, where the only leaves are the empty sets and order and multiplicity of branches is ignored. Equivalently, they can be seen as finite strings of balanced brackets modulo reordering and duplication of balanded substrings.

Finitary pure sets turn out to be convinient substrate to model any other finitary objects including natural numbers, finite sets of natural numbers, finite lists of natural numbers, rational numbers, graphs, finite groups, finite geometries, etc. For example, natural numbers can be modelled by sets containing models of all smaller natural numbers. Thus, zero is modelled as the empty set ∅, the number one by the set {∅}, the number two by {∅, {∅}}, etc. Given two natural numbers modelled by sets $n$ and $m$, one can model their ordered pair by the set { $n$, { $m$ } } which can be naturally extended to finite lists.

The theory of finitary pure sets (where no infinite set can be shown to exist) was first developed very recently [Pakhomov2019]. It is called $H_{<ω}$ and it has quite remarkable foundational properties. It is an excemption to the infamous Gödel’s second incompleteness theorem theorem that states that no strong enough mathematical theory can prove its own consistency. Pakhomov’s set theory $H_{<ω}$ is weak enough to evade Gödel’s theorem and does indeed prove its own consistency. Up to date, it is the only natural example of such a theory.

Yet, finitary pure sets are not enough to model real numbers or functions on natural numbers. How does one define infinite pure sets? The original Cantor’s idea was to try the same approach that works perfectly well for sets of integers, sets of reals and other “sets of $T$” within a typed framework, namely to identify sets and predicates on $T$. But pure sets are sets of pure sets, so the definition becomes recursive and leads to inconsistency of the theory.

For a period of time (1884–1899), the mathematical community was not aware of this inconsistency, and learned how inconceivably effective it is for modelling all sorts of mathematical objects. There were “enough” pure sets to model every mathematical object one could think out. In a sense, there were too much of them: the universe of sets was too huge to be charted in any useful way. Cantor himself compared it to an abyss way beyond comprehension.

After the inconsistencies (cf. Russell’s paradox) were exposed, the community did not abandon the pure set theories as a possible unified single-sorted (everything is of type “pure set”) foundation for the whole body of mathematics, but found other approaches to define enough infinite pure sets without introducing inconsistency.

One of such approaches, namely the one developed mainly by Zermelo and von Neumann (ZN), leads to a foundationally attractive class of set theories. There, one looses the ability to reflect all predicates on pure sets by sets themselves, but gains an insight into how sets are “built from below”. These are the ZN-type set theories, where one restricts the universe of discourse to wellfounded pure sets $S$ that are not allowed to harbour infinite membership chains

\[S ∋ S_1 ∋ S_2 ∋ ···\]From this point on, I will use the word “set” to mean wellfounded pure sets only.

Wellfoundedness precludes the existence of the set of all sets, as it would necessarily contain itself, $V ∋ V ∋ V ∋ ···$, in an infinite membership chain. In these theories, every set still defines a predicate (_ $∈ S$) on all sets and is completely defined by this predicate, that is two sets containing the same elements are the same set. However, it is not true anymore that every predicate defines a set, since the predicate $φ(x)$ = true would define a non-wellfounded set $V$ of all sets. Nevertheless, in ZN-type set theories one can still restrict any set $S$ already proven to exist by an arbitrary predicate $φ(x)$, that is form its subset { $x ∈ S | φ(x)$ }.

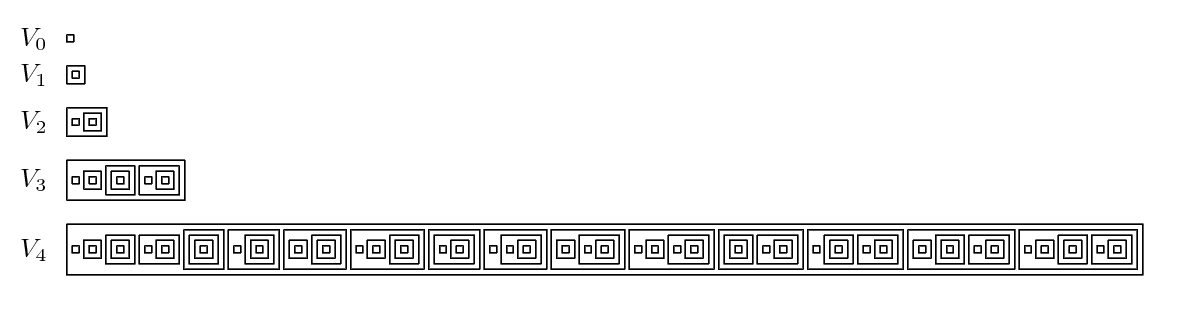

As already mentioned, the most appealing foundational feature of ZN-type set theories is that the universe of all sets can be better understood. Sets $S$ can be ordered by their “complexity” $rk(S)$, so that the collection of sets with complexity below $β$ forms a set $V_β$. Therefore, one has an infinite hierarchy of ever growing sets, known as the von Neumann hierarchy \(V_0 ⊂ V_1 ⊂ ··· ⊂ V_β ⊂ ···\) such that every set eventually enters the hierarchy, namely at the stage $rk(S)$ + 1. Therefore, the universe of all sets, which is not a set itself as it was discussed above, can be seen as the limit of this hierachy. Furthermore, all stages of the hierarchy can be explicitly described in terms of smaller stages.

Let us first consider finite stages of the the von Neumann hierarchy. The set $V_0$ of sets of complexity below zero should be obviously empty:

\[V_0 := ∅\]The set $V_{β + 1}$ of sets of complexity below $β + 1$ can be described in terms of sets of lower complexity. Namely, given the the stage $V_β$, let the next stage be

\[V_{β + 1} := 𝓟(V_β)\]where $𝓟(V_β)$ denotes the power set of $V_β$, i.e. set of all subsets of $V_β$ including $V_β$ itself.

With these definitions, one obtains an infinite sequence of sets satisfying

\[V_0 ⊂ V_1 ⊂ ···\]and

\[V_0 ∈ V_1 ∈ ···\]Each stage $V_β$ is a transitive set, that is it contains all the elements of its elements

\[(S ∈ V_β) ⇒ (S ⊂ V_β)\]and is closed under restricting its elements by arbitrary predicates $φ(x)$:

\[∀(S ∈ V_β) ⇒ \\{ x ∈ S | φ(x) \\} ∈ V_β\]The sequence $(V_0, V_1, …)$ can be continued transifinitely: one can form the union $V_ω$ of all these stages and show that it is also a transitive set closed under { $x ∈ S | φ(x)$ }, and contains all finite hierarchy stages both as elements and as subsets. $V_ω$ is the set of all finitary wellfounded pure sets, but it is not the end of the hierarhcy. One can iterate the powerset operation futher and to obtain $V_{ω + 1} := 𝓟(V_ω)$, $V_{ω + 2} := 𝓟^2(V_ω)$, etc. This sequence has a limit as well, which is given by the union of all its elements. This process can be iterated transfinitely for all ordinal numbers:

\[V_κ := ⋃_{β < κ} 𝓟(V_β)\]Due to wellfoundness of all sets one can now define the ordinal valued function measuring set complexity:

\[\text{rk}(x) := ⋃_{y ∈ x} \\{ \text{rk}(y) \\}\]It determines the stage of the von Neumann hierachy containing or equal to $x$. One can show

\[∀(S) S ∈ V_{\text{rk}(x) + 1}\]which proves the claim that every set eventually enters the hierarchy at some stage.

Each $V_β$ is a model of a weak set theory because it is a transitive set of wellfounded sets closed under restriction by arbitrary predicates. For each infinite ordinal $β$, $V_β$ models the theory of finitary sets $H_{<ω}$. For each limit ordinal $λ$, $V_λ$ is also closed under forming singleton sets ( $x$ ↦ { $x$ } ), ordered pairs (( $a$, $b$ ) ↦ { { $a$ }, { $a, b$ } }), and arbitrary unions, thus modelling an even stronger set theory. A ZN-type set theory $T$ capable of expressing $V_β$ for $β < κ$ for some infinite $κ$ can be modelled, and thus shown consistent, in another ZN-type set theory $T’$ capable of expressing $V_κ$. The reverse is not possible, since it would allow to construct the model of $T’$ inside of $T’$ itself and thus prove its own consistency which violates the Gödel’s second incompleteness theorem. Therefore, the ability to express $V_β$ up to a certain limit $κ$ linearly orders ZN-type set theories by their modelling capacity (also known as consistency strength).

The standard Zermelo-Fraenkel set theory ZFC is the canonical example of a ZN-type set theory, and is being used as the foundation for the majority of mathematics since its develpment in 1925. For some branches of mathematics such as category theory and algebraic geometry a slight extension of ZFC called Tarski–Grothendieck (TG) set theory is used instead. There, one additionally assumes that every set $S$ is contained in a stage $V_κ$ of von Neumann hierarhcy that is is closed under all possible set operations of ZFC. This property is technically refered as $V_κ$ being an inner model of ZFC.

ZN-type set theories are the canonical substrate for modelling various mathematical objects, and that is precisely what makes them interesting for sturcturalists who do not treat them as the foundation of all mathematics anymore. When a type theorist needs to prove consistency of a strongly impredicative type theory, such as System F or the observational calculus of constructions $CC_{obs}$, they resort to ZN-type theories to build models.

§§ Weak set theories

In the early days of set theory, everybody was primarily concerned with making theories general enough to model everyting of mathematical interest. Initially, there was a hope that after such an ultimate system is discovered, one would be able to prove its consistency using a weak system dealing only with finitary objects by means of minimalistic system of obviously non-problematic axioms. It was a part of a large program aimed at developing secure foundations for mathematics proposed by D. Hilbert. Soon it was proven by K. Gödel, that no powerful mathematical theory could prove its own consistency let alone consistency of stronger systems. Mathematicians with interest for secure foundations resorted to the second best option: to identify the weakest possible system that allows to express and prove the quintessential theorems of a particular branch of mathematics, and stay within this system. The search for the weakest systems capabale of expressing and proving certain results is known as Reverse Mathematics.

While some of the modern mathematics requires an extension of the standard ZFC (mostly TG), all mathematics pursued until the WW2, except the set theory itself, does not require the full power of ZFC. For ordinary mathematics, it is sufficient to work in a subsystem of ZFC, where the existence of von Neumann hierarchy stages beyond $V_{ω + n}$ (where $n$ is a fixed integer) cannot be shown. An even weaker subsystem with no constructible stages beyond $V_{ω + 1}$ is sufficient to prove theorems of algebra and combinatorics restricted to countable structures, and theorems of analysis and topology restricted to separable spaces. It is sufficient for the entire body of real analysis. Peano arithmetics is equivalent to a system where only $V_ω$ can be demonstrated to exist.

One can go even below that. The theory of finitary pure sets $H_{<ω}$ mentioned above is a ZN-type set theory well suited for modelling finitary objects without being able to prove existince of $V_ω$. This theory only contains finite stages of the von Neumann hierarchy. Extending this theory by an axiom postulating existence of $V_ω$ makes it equivalent to Peano arithmetics. All classical ZN-type set theories are extensions of the $H_{<ω}$.

Extensions of $H_{<ω}$ by axioms postulating the existence of specific infinite von Neuman hierarhcy stages seem to be the perfect base for reverse mathematics above $V_{ω + 1}$. All mathematical theories known to date can be modelled in some theory $H_{κ}$ that is an extension of $H_{<ω}$ by an axiom postulating the existence of a von Neuman hierarchy stage with some specific closure propertes which the universe of all sets can be thought to share as well. The ordinal $κ$ used as the parameter in $H_{κ}$ of these theories is not a fixed ordinal, but an ordinal capturing the desired closure propertes for each specific theory. As it was already mentioned, theories $H_{κ}$ are linearly ordered by their modelling capacity $κ$.

To give a specific example, consider the set theory ZFC. ZFC without the axiom of infinity $∃ω$ can be modelled in $H_{ω} = H_{<ω} + ∃V_ω$, i.e. axioms of ZFC without the axiom of infinity only require such closure properties that the set of all finitary sets has, and we assume that ZFC (including $∃ω$) only requires closure properties that the class of all (wellfounded pure) sets can be thought to share as well. Now, by $H_{κ_{ZFC}}$ let us denote $H_{<ω}$ extended by an axiom postulating the existence of a set that models ZFC. This theory models by ZFC definition. The theory $H_{<κ_{ZFC}}$ defined as $H_{<ω}$ extended by a family of axioms postulating the existence of sets modelling each finite set of formulas derivable in ZFC is by definition bi-interpretable with ZFC. Instead of ZFC we could have taken any recursively enumerable set of formulas admissible in $H_{<ω}$.

By providing a model of an arbitrary theory $T$ inside some theory $H_{κ}$ one obtains a strict upper bound $κ$ for its modelling capacity. By modelling the set theory

\[H_{<η} := H_{<ω} + ∃V_β \text{ for each } β < η\]inside $T$, one obtains a lower bound $η$. By establishing the bi-interpretability of $T$ with some $H_{<κ}$, one determines the exact modelling capacity without establishing the bounds.

§§ The theory of finitary pure sets $H_{<ω}$

The theory of finitary pure sets by F. Pakhomov $H_{<ω}$ is stated in the language of single-sorted first order logic with equality extended by the binary relation (∈) and the unary operator $V$. To be specific, the language of the first order logic with equality consists of the usual logical operators (¬_), (⇒), (∧), (∨), the quantifiers ∀ and ∃, and the equality (=). Single-sorted means that all variables are of the same type (“wellfounded pure set”, in this case). Beside these basic parts of syntax, the language of $H_{<ω}$ has a binary relation $a ∈ b$ and a unary operator $V(x)$ denoting the smallest stage of von Neumann hierarchy containing or equal to $x$.

The theory has all the axioms governing the logical elements of the language (¬_, ⇒, ∧, ∨, ∀, ∃, and =) including double negation elimination $¬¬P ⇒ P$. In addition, it has a countably infinite family of axioms postulating the existance of the sets $V_n$ for each individual finite $n$, the axiom of extensionality specifying equality between sets

\[(a = b) ⇔ ∀x ( x ∈ a ⇔ x ∈ b )\]the axiom schema of separation that allows to restrict any set $x$ by an arbitrary predicate $φ(z)$

\[∃y ∀z (z ∈ y) ⇔ (z ∈ x ∧ φ(z))\]and the defining axiom for $V$

\[y ∈ V(x) ⇔ (∃z ∈ x)(y ⊆ V(z))\]By Gödel’s second incompletness theorem, if a theory $T$ is capable of modelling natural numbers so that at least one strictly monotonously growing function on them can be proven injective, than $T$ cannot prove its own consistency. The theory $H_{<ω}$ is carefully formulated to be non-Gödelian: it does not provide a way to show the existence of infinitely growing functions unconditionally. For example, one cannot show that “for any two integers $a$ and $b$, there exists their product $a · b$”. Yet, one can still prove all such statements conditionnaly on the existence of what can be interpreted computationally as the “availability of enough memory to carry out the construction”. In particular, one can show that “for any two integers $a$ and $b$, given enough memory, the integer $a · b$ exists”. Metatheoretically, it can be shown that any true arithmetical or combinatorial statement can be proven in this theory, if an upper bound on the memory required to carry out the underlying constructions can be provided.

To date, the theory $H_{<ω}$ is the best candidate for the finitistic core for metamathematical reasoning seeked by Hilbert in his program: a weak system dealing only with finitary objects by means of a minimalistic system of axioms. Due to Gödel’s theorem, it cannot be used to prove other theories consistency unconditionally but it at least proves its own consistency. It can be used to prove the consistency of other theories conditionaly on existence of suitable infinite stages of the von Neumann hierarchy. It is, however, unclear if it is suitable for more fine-grained conditional consistency proofs used in reverse mathematics below $V_{ω + 1}$. There, one deals with a dozen theories with modelling capacities either strictly below $H_{ω}$ or strictly between $H_{ω}$ and $H_{ω + 1}$. Their consistency proofs are currently carried out in a weak system called ERA (elementary recursive arithmetic) and are conditional on termination of specific recursive algorithms rather than existence of specific infinite sets, which provides the required granularity. We still have to try out how to state recursion termination properties and carry out consistency proofs conditional on them in $H_{<ω}$.

We conjecture that a refinement of $H_{<ω}$ based on intuitionsitic logic might prove to be a better candidate for fine-grained conditional consistency proofs than both the classical $H_{<ω}$ and ERA.

§§ The constructive set theory CZF

The other weak set theory extensively used for modelling mathematical objects is the constructive set theory CZF. It was introduced in 1978 by P. Aczel as a constructive counterpart of the standard set theory ZFC. It is formulated in the language of single-sorted first order theories with equality extended by the relation (∈), but it is an intuitionsitic first order theory. The axioms governing the logical operators to not include double negation elimination (DNE) $¬¬P ⇒ P$. CZF is a weak predicative theory; its modelling capacity of lies strictly between $H_{ω}$ and $H_{ω + 1}$. CZF is that can be modelled in a rather weak Martin-Löf type theory and proven consistent relative to termination of algorithms defined by $ψ(ε_{Ω+1})$-recursion. In the presence of double negation elimination modelling capacity of CZF skyrockets:

\[CZF + DNE = ZF\] \[CZF + \text{Axiom of Choice} = ZFC\]CZF was designed as a system for modelling mathematical objects in the constructive setting. It is used to model algebraic model strucutres on simplicial and cubical sets in category theory and predicative constructive type theories.

Since CZF lacks the powerset operation, which is substituted by a much weaker subset collection axiom, the von Neumann hierarchy in its original form cannot be defined for CZF. Recently, Zieger (2014) managed to define a modified von Neumann hierarchy that shares the property that all sets eventually enter the hierarchy, and thus gives the same foundational security CZF. Modified hierarchy conicides with the usual one in presence of double negation elimination. With this result, one can consider CZF to be ZN-type set theory. Much like in the case of $H_{<ω}$, the modelling capacity of CZF itself is not always sufficient for modelling all objects of interest, but it can be extended by postulating the existence of a modified von Neumann hierarchy stages $V_κ$ having specified closure properties which the universe of all sets can be thought to share as well.

§ Towards Constructive Theory of Finitary Pure Sets

All true propositions of $H_{<ω}$ about finitary sets are provable in CZF as well, but $H_{<ω}$ is not a subtheory of CZF because it is defined over first-order logic with double negation elimination, which is not present in CZF. Adapting $H_{<ω}$ to constructive setting is a nontrivial and intriguing task. The axiom of extensionality and the axioms postulating existence of all individual finite level stages of the von Neumann hierarchy can be taken over literally. The axiom schema of separation can be substituted by predicative separation, which is known to be implementable by a finite number of axions instead of a schema. The tricky part is the definitional axiom for $V$ (see below).

Following the approach of von Neumann-Gödel-Bernays set theory, such a theory can be conservatively (i.e. without introducing new theorems or increasing strength) extended to include not only sets but also classes of sets that directly reflect predicates. The resulting theory remains single-sorted, with every variable being of the type “class of sets”, and sets being recovered as such classes $S$ that belong to at least one other class $C ∋ S$. Such modification allows to handle all objects of interest without resorting to a second-order extension of the theory used in the original paper by F. Pakhomov. We conjecture that the resulting theory (let us call it $CGB_{<ω}$) would be even more suitable for the role of finitistic core for metamathematical proofs.

When proving that two theories are equiconsistent or one theory being consistent conditionally on certain ordinal notation being wellfounded, one seeks to use the weakest system possible. Today most metatheoretical proofs are carried out in the system known as Elementary Recursive Arithmetic (ERA). $CGB_{<ω}$ it is much weaker while still allowing reasonably comfortable manipulations with finitary data (like derivation trees) encoded as finitary sets and recursive algorithms (such as cut elimination).

While being equivalent to a first-order theory, ERA can be formulated as a stanalone logic-free calculus involving only functional symbols and judgements of the form “ $P = Q$ ” in an aesthetically pleasing and minimalistic way: it has only four inference rules besides symbols and defining equations for all definable elementary arithmetic functions.

In the second part of this paper we outline how to present $CGB_{<ω}$ in logic-free all judgements of the form P ⊃ Q.

Unfortunatelly, the system as presented there is far from being as minimalistic as ERA.

However, the initial standalone formulation of primitive recursive arithmetic was also far from

being optimal; it took another decade to streamline it to the present aesthetically pleasing form.

It might work out for $CGB_{<ω}$ as well.

§ Mechanizing metatheoretical proofs

Both ERA and conjectural $CGB_{<ω}$ are not directly suitable for carrying out metatheoretical proofs because the syntax of the respective theories is only accessible through some kind of arithmetical encoding which is itself nontrivial and error prone.

In our work on Higher Observational Constuction Calculus, we show how formalized languages containing bound variables can be naturally and directly represented by indexed purely inductive types: these are types freely generated by a set of grammar rules. This approach covers both the languages of first-order theories (both single-sorted and multisorted), and the languages capturing (natural deduction) proofs in those theories. The latter languages are necessarily dependently-typed, where proof terms are typed by propositions they prove. The ability to capture languages and manipulate their terms in a direct and convenient manner makes construction calculi the best framework to carry out metamathematical proofs. The apperent downside is that construction calculi are very far from being minimalist.

Yet, as we outline in * is more than Type, inductive definitions can be also seen as a kind of macros defining objects in any category $C$ with sufficient structure that can be defined in the underlying construction calculus. Within this approach also manipulations involving terms get decoded (“macro expanded”) into elementary constructions available in the category $C$. We hope to be able to define the category exactly corresponding to the set theory the $CGB_{<ω}$, and show that it has enough structure to model enough indexed purely inductive types. That way direct style metamathematical proofs in HOCC (where one manipulates the real syntax and not its arithmetic encoding) get compiled into $CGB_{<ω}$ proofs where finitary objects of obvious structure are manipulated within minimalistic foundationally secure theory.

§ Supposed Logic-free Calculus for $CGB_{<ω}$

First let us formalize the theory $CGB_{<ω}$ without $V$ operator and its definitional axioms

as a standalone logic-free calculus. In this setting, all terms will represend class-valued

operators of zero or more variables, all judgements will be of the form X ⊃ Y, where X

and Y are terms.

There is no equality judgement in this formalism, so there will be no axiom of extensionality.

Instead, every proposition requiring two classes X and Y to be equal will be explicitly

requiring both X ⊃ Y and Y ⊃ X.

Let us start by listing the inference rules governing equality and substitution:

------- Reflexivity

P ⊃ P

P ⊃ Q Q ⊃ P

---------------- Inner substitution rule

F(P) ⊃ F(Q)

F(x) ⊃ G(x) G(y) ⊃ F(y)

--------------------------- Outer substitution rule

F(z) ⊃ F(z)

The transitivity rule will turn out to be derivable form others, but let us also mention it for sake of completness:

X ⊃ Y Y ⊃ Z

----------------- Transitivity

X ⊃ Z

Now we need to introduce the constants 0 = {}, 1 = {0}, and a binary operator

𝔼(x, y) = { $x ∈ 1 | x ∈ y $ }. The proposed definitions are not how we introduce

them, they are there only to explain the intended meaning of those symbols.

We’ll also introduce the following two judgement abbrevations:

1 ⊃ 𝔼(x, y) will be denoted by x ∈ y.

𝔼(x, y) ⊃ 0 will be denoted by x ∉ y.

Now let’s give the rules for those three objects.

----- Empty set is subclass of every other class

S ⊃ 0

x ∈ 0

----- ex falso quodlibet (if empty class contains something, than anything contains everyting)

y ⊃ z

----- 1 contains 0

0 ∈ 1

x ∈ 1

----- 1 contains only subsets of zero (thus only zero)

0 ⊃ x

-------------

1 ⊃ 𝔼(x, y)

X ⊃ Y

-----------------

𝔼(s, X) ⊃ 𝔼(s, Y)

The last axiom does not characterize the relation between membership and being superset completely.

We need to express the inversion. We’ll only be able to express this property later, after we learn

how to introduce quantifiers. So first we have to introduce propositional logic. We already can

encode propositions false, true and (x ∈ y) as subsets of 1, now we have to introduce conjunction

A ∩ B, disjunction A ∪ B and implication A ⇒ B operators producing subsets of 1 if A and B are.

As for implication, we can simply take

------------

(A ⇒ B) ⊃ 1

X ⊃ Y

============

1 ⊃ (A => B)

Together with transitivity this definition implies modus ponens. If we now state the 8 Hilbert style axioms for intuitionsitic logic, we obtain the full intuitionsitic propositional logic.

We are also ready to generalize the conjunction and disjunction from subsingletons to any classes by the following rules:

x ∈ (A ∪ B)

=========================

1 ⊃ ( 𝔼(x, A) ∪ 𝔼(x, B) )

x ∈ (A ∩ B)

=========================

1 ⊃ ( 𝔼(x, A) ∩ 𝔼(x, B) )

Now we can define the finite ordinals, that is constants 2, 3, 4, etc in addition to 0 and 1 which we

already have defined. The ordinals will by an axiom scheme that also defines sets {0}, {1}, {2}, etc.

We treat these {n} as names of constants, we do not define the operation {_} as it would ruin the

non-Gödelianess of the theory.

-------

n ∈ {n}

x ∈ {n}

-------

x ⊃ n

x ∈ {n}

-------

n ⊃ x

------------------

n' ⊃ ( {n} ∪ n )

-----------------

( {n} ∪ n ) ⊃ n'

Finaly let’s deal with classes and predicates. Let us define unary operators ∀ and ∃ as well, and for any term φ(x,..,z) of our system with (n + 1) variables define the n-ary operator { x | φ(x,..,z) } together with following axioms

C ⊃ φ(x,..,z)

------------------------ ∀-Intro

C ⊃ ∀{ t | φ(t,..,z) }

------------------------------- ∀-Elim

∀{ t | φ(t,..,z) } ⊃ φ(x,..,z)

φ(x,..,z) ⊃ C

------------------------ ∃-Elim

∃{ t | φ(t,..,z) } ⊃ C

------------------------------- ∃-Intro

φ(x,..,z) ⊃ ∃{ t | φ(t,..,z) }

Now we can finally fix the relation between being member and subset:

-------------------

X ⊃ { x | 𝔼(s, X) }

-------------------

{x | 𝔼(s, X) } ⊃ X

Now let us try to define the V operator inverting the definition of modified von Neumann hierarchy from “Large Sets in Constructive Set Theory” by Albert Zieger along the lines of axiom 3 on the page 3 of “A weak set theory that proves its own consistency” by Fedor Pakhomov:

y ∈ V(x)

==============================================================

∃{z| 𝔼(z, x) ∩ (V(z) => y) ∩ ∀{t | ( V(z) ∪ 2) => 𝔼(t, y)} }

For Δ₀ formulas φ(x,..,z) we additionally postulate separation in the following form

y ∈ V(x)

-------------------------------

(y ∩ { t | φ(t,..,z)}) ∈ V(x)

Next steps:

- Show that this theory proves set induction or add it

- Ensure this theory proves excluded middle for finitary sets and establish connection with $H_{<ω}$

- Show that for each A, B ∈ V(x) ∈ V(y), their subset collection C can be defined and C ∈ V(y)

- Explore what kind of set theory emerges if an infinity axiom is added

- Explore the relationships with strong collection